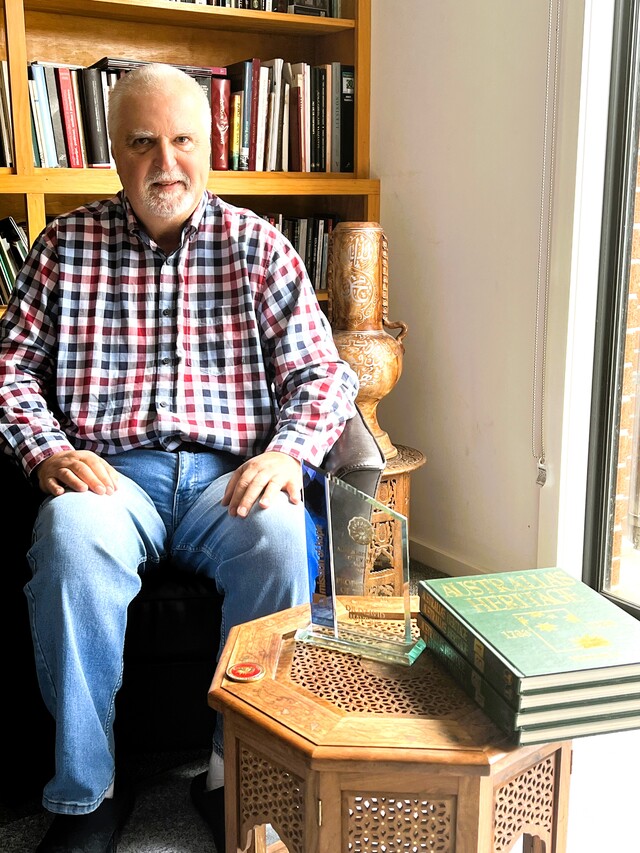

Dr Dzavid Haveric is Adjunct Research Fellow at Charles Sturt University, Centre for Islamic Studies and Civilisation and a leading expert on the history of Islam and Muslims in Australia. He is the author of 13 books and a Research Associate at Museum Victoria. He speaks with JUSTIN FLYNN about his upcoming book that extensively documents the history of Muslim Australians and their descendants in war.

As I sit down in Dr Dzavid Haveric’s Charlemont home it is immediately obvious he is looking forward to our conversation.

His eyes gleam with anticipation as we settle in to discuss his new book that focuses on Muslim Australians at war. Even his dog Hugo seems to look forward to it as he curls up at my feet in the loungeroom.

Announced as Australian Muslim Professional of the Year in February, the research Dr Haveric put into this labour of love was, according to the man himself, “thousands of hours… endless”.

The book, ‘History of Muslims in the Australian Military from 1885 to 1945’, took Dr Haveric to almost every corner of the country. He spoke to descendants of Muslim soldiers, talked to their friends, visited libraries, museums and RSL Clubs, walked through cemeteries, spoke with scholars, and collected diaries, photographs and letters.

The project received the backing of the Department of Defence and Charles Sturt University.

Dr Haveric began researching the book back in 2018. A visit to a lonely headstone of a Muslim soldier inspired the project.

“This is a very original topic,” he proudly says.

“Nothing is written about it and if someone is trying to do the same they can only follow my references. This is why I’m emphasising the originality of my project and if someone wants to do research on that subject, then they can only follow my footpath.

“But on top of everything, my book will be a great reference for all scholars, to universities, to museums, to RSL clubs, to war memorials and on an international level as well.”

Dr Haveric immigrated from war-torn Bosnia in the mid-1990s. His love for Australia and its people from all walks of life and religions is evident.

“My love for the country inspired me and the reason why I decided to do this project is simply because I was very challenged to produce an original piece of work and to enrich Australian social military history,” he says.

“This is a wonderful nation and I wanted to contribute as a professional historian. I wanted to contribute with this project and to show all Australians, not just Muslims, to all fellow citizens and to the world that we are great.”

Dr Haveric shares his name with his uncle, who is a national hero in Bosnia.

“My uncle is the very first Muslim who fought against the Nazis in the Second World War,” he says.

“He is a national hero and I got his name in his honour.”

Not much has been documented of Muslim Australians in the defence force.

“They were proud to serve,” Dr Haveric says.

“They were highly regarded by their Australian mates. They got great recognition for their contribution. Some of them lost their life because they wanted to fight for Australia.

“Their willingness to respond to the call and their patriotism and their loyalty and their contribution and their sacrifice was for a noble cause.

“They fought together with other followers of other nationalities or other religions or other cultures, not necessarily religious beliefs, but cultures, because there are some atheists as well.

“According to Islamic doctrine it is the duty of Muslims to defend the country, even against a Muslim country.”

Dr Haveric says many Muslim Aussies were denied the chance to defend their country due to the White Australia policy.

“The reason why there is not a larger number of Muslims in the Australian army is because White Australia policy didn’t allow them,” he says.

“(But) when they did join, they found a sense of equality and they willingly accepted the call and they contributed in their way as a minority group. They were very proud and very keen to do their bit.”

Muslim Australians and their descendants weren’t just restricted to combat either.

“A lot of women were also involved in sewing uniforms and some were herbalists who offered their help to heal wounded soldiers,” Dr Haveric says.

“Women also contributed in hospitals. There are also those who gave their last penny.”

Dr Haveric baulks when asked how many Muslims served, insisting it will be revealed at the book launch soon.

Instead he says that he had to approach some topics with extra sensitivity.

“(There are) many stories of Muslims of many different backgrounds, different sects, you have to approach people of different sects (and) it’s not always easy,” he says.

“You have to have cultural sensitivity. You have to have knowledge of other sects because Islam is heterogenic. It’s not monolithic, you know.

“In Islam it’s a complex topic. So I have brought many stories. Some stories are touching stories, sad stories, some are happy stories.”

I go off on a tangent as I am served some delicious cake with strawberries and fresh cream and say that my Italian grandfather, who served in WWII for Australia, went from Giovanni to John after he immigrated from northern Italy.

Dr Haveric says many Muslims also took anglicised names to fit in and just because they were easier to pronounce and remember.

“Like myself, people calling me David, but I’m Dzavid (pronounced Javid),” he says.

“If someone doesn’t remember my name I just say ‘call me David’, but I love it if someone really calls me Dzavid.

“So many of them were with unrecognised names. Like Hussein was called Bob or they were Jack, Jimmy, John, Mark.”

The book is in its final stages of typesetting and awaiting its launch. Its subtitle is ‘loyalty, patriotism and contribution’.

I wonder whether that goes some way into summing up Dr Haveric himself.

The last thing I ask Dr Haveric is whether this will be his legacy.

“There will never be another book like this ever,” he says.